Wielerparcours

Discussiehoek

Mountain Biking

Wielerparcours

Discussiehoek

Mountain Biking

text en photographs: Robert van Weperen

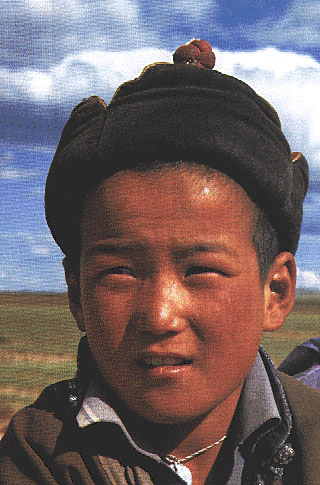

Magnificent Mongolia

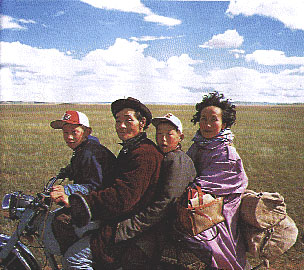

A bike in Mongolia!? It has to belong to a foreigner. There is however no lack of saddles in this country! On the contrary, the Mongolians are practically born in the saddle but it's the one firmly fixed to the back of one of their high spirited, sturdy little horses.

I've scarcely set foot in the arrival hall of the airport at Ulaan Baater when a

friendly slant eyed boy pushes a piece of paper into my hand. I read, in authentic

Remington typed letters:'Welcome to Mongolian, I am yours guide'.

'How do you know it's me ?', I ask, surprised by his self-assurance. In

answer he points at the large cycle box I'm trailing behind me and says, 'Cycle -

Holland!'

Holland - Cycleland, is making a name in Mongolia. A week previously a group of

thirteen Dutch cyclists had begun a thousand kolometre tour of this country which is

just opening up to the outside world and whose area is thirty-six times that of Holland.

Thirteen of the tens of thousands of Dutch people who participate in an 'organised'

cycle trip every year. I'm following them with a camera around my neck and a pencil

behind my ear.

Chinese comrades

Esconsced in an ex-DDR army jeep Mandaa, my guide, and I travel towards the capital. Mandaa is surprised when I recognise the towering power station on the outskirts of the city - it was on a tv documentary in Holland last night!A day later the same reincarnated jeep takes us to Tsetserleg where the group of cyclists ought to be if all has gone according to plan. The first 300 kilometres are on a made-up asphalt road which is actually a strip of bitumen with all the characteristics of a Dutch cheese that has been attacked by an army of mice. This 'highway' was laid down by Chinese comrades a quarter of a century ago. The next 150 kilometres are covered on a dirt road speckled with rocks and grit alternating with patches of deep liquid mud. I make a mental note that this is great country for cross country cycling as I crouch, hunched up in a corner of the jeep as the driver wrestles with the steering wheel

Feel the country = see the country

We don't get wet in the jeep but as we arrive in Tsetserleg the next day, we see that the group has not been so fortunate. Camped out on a slight slope they found that the Mongolian tents were not proof against the Mongolian rain. The atmosphere in the group however has not been affected and the cyclists are enthusiastic about the route, the beauty of the country and the generous hospitality shown by the Mongolians along the way.The next day, when I'm in the saddle of my hybrid bike I can tell that they have not been exaggerating. Although the jeep afforded a good view of the countryside I had missed the feel of the country. You can only get to know the country by feeling it and the best way to do this is, as far as I am concerned, is to get on a bike.

Taking our time we cycle along a sandy track winding through the undulating countryside that, bearing out the words of the guide books, is as green as grass. Grass is literally the only thing that grows in this area. I haven't seen a tree all day and get the feeling that we're cycling through the world's largest huge golf course on which work has stopped through lack of funds.

Yellow lumps

The feeling of being alone is complete: there is no living creature to be seen, or are there? As my eyes become accustomed to the overpowering greenness I can distinguish three white dots in the distance, like flying saucers. Half an hour's cycling later they turn out to be the so-called gers, a Mongolian nomads' dwelling. The whole family, who have probably seen me coming from a distance, father mother and four chidren are waiting outside.I sit on a stool in the middle of the tent trying to recover my wits after whacking my head hard on the low doorframe of the tiny door. Father and children sitting on the beds arranged in a circle around the walls of the tent observe me as mother fills a Chinese porcelain bowl with milk. Using both hands she gives it to me and I, contrary to all the rules of local etiquette as I later discover, accept it with one hand. It smells a little sour and has yellow lumps swimming around in it, but is extremely refreshing. It's called Aryak, fermented horse milk - inviting, invigorating, inspiring. Eyes closed I taste champagne, eyes open I'm in Mongolia.

Tony Thunderbird

Two days later. The itinerary, drawn up by our Dutch guide Rik Idema tells us: 'On your right, a house, turn left here, follow a barely defined trail'. Even without this detailed itinerary I would have no trouble finding the way. Strung out towards the horizon there is a line of cyclists. Wim is probably leading them with Richard and Pieter hard on his heels closely followed by Cees Cuba (can't talk about anything else), Tony Thunderbird (had a nasty fall with his Koga with its balding 27 inch tyres) Gabby Gail and all the rest.Flamethrower

Lunchtime: Peanut butter sandwiches, sausage and Dutch chocolate drops provided by the baggage/provision truck which is waiting for us half way. We all sit on a plastic table cloth and tell our stories. Pieter can hardly contain himself as he tells how he was almost caught up in a stampede of wild horses that came galloping out of the foothills. Wim, a man of few words, can't say any more than 'brilliant', and Marjan, the shyest of girls relates how she was tempted into a tent by two friendly Mongols. Not for her the bowl of horse milk but a cup of tea, with milk and salt! 'I think I'm getting to like the taste' she remarks bravely, but just like the rest of the group she enjoys her cup of Dutch tea and the tasty pasta meal prepared by the cook and his assistants.This cooking group consists of the driver, his wife and a cook. The three of them take care of the groups' eating needs. Not an easy task considering that the shops aren't exactly plentiful in this sparsely inhabited corner of the world. You can't even buy bread during the 300 kilometre, 5 day stage, from Tsetserlag to Bulgan. As well as a large store of food the cook has a load of kitchen paraphernalia to take care of. He's got a cart load of thermos flasks and a kerosine burner that is half way between a welding apparatus and a flame thrower. This formidable metal dragon doesn't go under the pan but the flame is directed horizontally at the side. It looks dangerous but who cares? The meals that it produces are delicious and keep us in the saddle and pedalling. In spite of the Mongolian hospitality we couldn't have kept going in this immense country without this culinary support team.

Hard baked plastic

During the day it can get hot in Mongolia and sun cream is an important item, but at night the temperature can drop to 5 degrees. A sweater, yes, I had thought of that but I've never been the proud owner of one of those super insulating polar sleeping bags. Bad news, because the nearest hotel is three hundred kilometres down the road. During the evening meal we are visited, as usual, by a small group of Mongolian horsemen. Our interpreter, Tseren, arranges, as usual, a place for me to sleep. A good excuse for me to be on my own for a while because whichever way you look at it, in a group, your thoughts drift back to Holland.I cycle through the pitch black night flanked by two horseman on their small horses. It must be a strange sight especially when I disappear over my handlebars when my front wheel gets stuck in a pothole. 'Noeg, noeg' they shout amused and concerned at the same time. 'Noeg' means hole and the the holes are dug by the numerous marmots that shoot past you as you cycle along. My arrival has not gone unnoticed and the inhabitants of the the three other gers join us. By the light of a few flickering candles the family photos I've brought with me go from hand to hand. Before going to bed I have to eat all sorts of things: fresh bread, aryak and hard baked plastic. The Mongolians probably have another description for this teeth breaker made from sun dried milk but I think I'll just stick to hard baked plastic.

gracious green rolling landscape

Early the next morning I would've liked to turn over and go back to sleep but the lads who have given up their bed for me are outside doing their morning exercises: chopping wood for the stove. Wood isn't the only fuel in this green expanse - horse droppings also find their way into the stove. The stove is placed in the middle of the ger and the red hot pipe sticks out through the roof. This morning the lady of the house is stirring in a steaming pan while the lord and master buttons up his coat. Not just any old coat: it's long and made from shiny material embroidered and with silver buttons. The sleeves are extra long for, I suppose, extra warmth and protection in the winter. This traditional clothing is worn by almost all the nomads. It's not like the traditional clothing worn in Holland that is only brought out on special days or as an extra attraction for visitors. No, this is functional and worn as casually as we wear jeans and t-shirts. Before I finally decide to roll out of bed and attire myself in my traditional cycling shorts I peep out of the less than adequate front door and gasp as I look out over 30 kilometres of gracious green rolling landscape - I can't wait to get out there.Oondoog doowy

Today's stage is 60 kilometres of hilly countryside following a cart track reinforced with the worst kind of stones as far as a bike is concerned. Within an hour I've had two punctures. Fortunately team spirit prevails and with my companions' help I'm back in the saddle in two shakes of a nomad's donkey's tail. I get my fourth puncture just as we are getting into the swing of the cycling so I, quite rightly, get left behind to fix my tyre in glorious solitude. That evening I put a Swallow tyre on the rear wheel and never have to use the repair set again.Next day is full speed, no brakes, downhill all the way to Julie Furtedo. An Emergency Stop in the middle of nowhere. The chain on Pieter's hybrid has snapped and the tool set has got everything except for a simple chain punch. In the mini-village we've stopped at, six tents in a line, you can't even get a horse shoed. The situation doesn't look so good but the bike gets turned upside down and the only available tools, a sledge hammer and chopping block are used to straighten out a rusty nail that grandma has discovered in a old Nivea tin. A few nervous moments later the nail is straightended and Pieter can ride his 'oodoog doowy', as they call a bike here, again.

Flintstones

More sensation: a sheep is being slaughtered for us. The cook hasn't been able to do any foraging for days so while we were busy repairing the halting hybrid, he was selecting a sheep. The beast is slaughtered 'humanely'. Two men grab hold of it and the one sitting between the animal's rear legs makes an insertion with a sharp kitchen knife near the heart. Then his hand goes in the hole feeling for the aorta. He finds it, pinches it and a second later the blood supply has been cut off and the animal dies. I follow this ritual from a respectable distance and my companions fill me in on the details later. However you can't deny that the Mongols show respect for the animal that gives its life so that we can eat. Hardly any blood is lost and the animal is carefully butchered. The next evening the the sheep is cooked according to the very finest Mongol traditions: together with fist sized river stones the meat is put into a sort of milk churn and placed on a wood fire. The stones ensure that the meat is cooked evenly. The container is closed to build up pressure, so opening it up takes three quarters of an hour and lots of patience and skill. The stones are the first to come out - red hot! - and following our hosts' example we roll the stones in our palms to absorb the power they have into our bodies. And then comes the meat, compared with which any Christmas Dinner enjoyed in the past pales into insignificance. The Flintstone sized hunks of meat are served up on plastic plates together with Schultheiss beer and the driver/cook completes the evening with a ballad sung from the depths of his heart. His song reaches out into the night and loses itself in the endless plains. The Dutch delegation feels obliged to reciprocate and sing the only song that everybody knows the words to: 'Op een klein stationnetje'(at a little station), not exactly the pinnacle of cultural excellence but never mind. The fire is replenished, another plate of meat, and we round the evening off with the 'International', everybody singing in his or her own language.Vodka in the bidon

The end of the cycle trip is at Erdenet, a large town (65,000 inhabitants). From here we travel 600 kilometres to Ulaan Baatar by rail. It is both a shock and a relief to be among so many people after the comparative solitude of the recent weeks. The train, 18 railway trucks drawn by a diesel locomotive, is probably the most densly populated spot in Mongolia but it's also pretty friendly with people popping in and out of each other's compartments to share the newly bought bread, cheese, sausage and fruit. Somebody produces a bidon full of pure vodka : eyes closed, mouth open and squeeze gently. I manage to wake up in my own compartment.Ulaan Baatar. They've got traffic lights here and a drainage system that leaves the streets awash after the first downpour. You don't have to hunt around for souvenirs. You can buy them all in one go at the gigantic department store. Mongol clothing, music and vodka. There is a natural history museum and a real disco where the drinks cost 2 dollars each. On the streets there are trolly buses and rickety Opels which have been driven overland from Germany. Even so you can still see the Mongol horseman riding through the streets with his typical headgear ending in a knot. In twenty-five years' time the Mogols will all have TV in their tents and communicate on internet but I'm sure that they'll still be riding their fierce little ponies, drinking aryak, playing dominoes and living in their gers. I'll go back, on a motor assisted pushbike, and keep you posted.